Rolling Stock Hall

Locomotives – Diesel

A Second Generation Diesel Locomotive

Class: GP-30

Built: 1963 by General Motors, Electro-Motive Division (EMD), La Grange, IL Illinois

Retired: 1984

The “Second Generation” of diesels met a growing demand for larger and more powerful diesels, designed for both high-speed and heavy low-speed freight trains. These improved locomotives were quickly replaced by even more powerful models and assigned to heavier mainline trains or yard and local switching jobs, making them old before their time.

The GP30 can be identified by its distinctively-styled roofline. Many crews disliked the cabs for their noise, poor heating, and lack of headroom.

Fun Fact: No. 2233 was one of the last locomotives painted Conrail blue by former employees at the former Pennsylvania Railroad/Penn Central/Conrail Juniata Shops.

The E7: An Efficient Diesel Electric

Click Here for Virtual Tours of the Engine Room & Engine Cab

Class: E7a

Built: 1945 by General Motors, Electro-Motive Division, La Grange, Illinois

Retired: 1973

Though initially unsure about the new diesel-electric technology and suffering from a lack of diesel refueling stations, the Pennsylvania Railroad was reluctant at first to put the new E7s to work. It quickly became apparent, however, that the new diesel-electrics operated with great efficiency and reliability. Almost immediately, orders went out to several manufacturers for new diesels to re-equip the entire “Blue Ribbon Fleet” of passenger trains.

Due to be scrapped shortly after retirement, quick thinking on the part of railroad employees saved the locomotive, hiding it for a time in an abandoned section of the Harrisburg roundhouse. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission raised the $20,000 scrap value to purchase it in 1976.

Fun Fact: The 5901 and sister engine 5900 were the first diesel-electric passenger locomotives built for and delivered to the Pennsylvania Railroad.

An All-Purpose Model

Class: GP-9

Built: 1955 by General Motors, Electro-Motive Division, La Grange, Illinois

Retired: 1985

The success of the GP9’s design can be attributed to its versatility and economy. The “GP” in the GP9’s name stood for “General Purpose.” Truly a general purpose model, these locomotives could switch freight cars in a yard one day, be coupled to other locomotives and pull a heavy coal drag the next, and finish off with a turn on a passenger train. The Electro-Motive Division of General Motors designed the locomotive to be operated easily in either direction.

This locomotive’s versatility and low-maintenance costs allowed it to outlive the Pennsylvania Railroad. It continued in service for Penn Central and Conrail.

Fun Fact: General Motors, Electro-Motive Division produced more than 4,000 GP9’s between 1954 and 1963.

Locomotives – Electric

A Powerful Locomotive Known as a “Brick”

Class: E-44a

Built: 1963 by Pennsylvania Railroad and General Electric, Erie, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1991

The E44 class electric, built with a silicon rectifier, delivered an amazing 5000 horsepower. Referring to its pair of three-axle trucks and boxy carbody, train crews often called the E44’s “bricks.” The unit served the PRR in freight service for five years before becoming part of Penn Central and finally Conrail.

Amtrak considered using the big electric for maintenance-of-way service on the Northeast Corridor until newer federal regulations addressing the use and disposal of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs), a toxic chemical used to cool the transformer, made its operation cost prohibitive. A sole unit, No. 4465, was officially turned over to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania on April 27, 1991.

Fun Fact: No. 4465 was the last electric locomotive built for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The GG1: The Most Successful Electric Locomotive Ever Built

Class: GG-1

Built: 1943 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops and General Electric, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1980

As the Pennsylvania Railroad embarked on its ambitious electrification project in the 1930s, it continued to develop and test new locomotive designs. The goal was to produce a new electric locomotive capable of pulling heavy passenger trains at speeds of up to 100 mph. The Pennsylvania Railroad chose the GG1 as the foundation of its new roster of electrics.

After a prototype was built, the Pennsylvania Railroad hired industrial designer Raymond Loewy to improve upon the overall appearance of the GG1 for the production models, like No. 4935. Among his many refinements to the look of the GG1 were their welded, instead of riveted, bodies and iconic “cat’s whiskers” pinstriping. When No. 4935 was restored in 1977 to its 1943 appearance and rededicated in Washington’s Union Station, Loewy placed his signature on the locomotive’s nose. No. 4935 also pulled the last run of a Railway Post Office in July 1977.

Fun Fact: Because the sum of its road numbers equaled “21,” crews nicknamed the locomotive “Blackjack.”

A New Style of Switcher

Class: B1

Built: 1934 by Pennsylvania Railroad in association with Westinghouse Electric & Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1971

Passenger trains required servicing at major terminals, needing to be broken apart, cleaned, serviced, inspected and reassembled for their next departure. The passenger coach yards needed small and powerful switchers that could be operated on the overhead electrified wires. As passenger revenues declined in the1950s and 60s, railroads scaled back on both electrified coach yards and these switching locomotives.

No. 5690 was constructed with the last group of B1 electric switchers, often running around the clock moving empty passenger cars across the yards. The No. 5690 spent most of its life in New York’s Sunnyside Yard.

Fun Fact: The B1’s earned the name “rats” by crews watching the way they shuffled around railyards as they switched cars.

Class: EPA

Built: 1931 by Bethlehem Steel Company, Wilmington, Delaware

Retired: c. 1980

On July 26, 1931, regularly scheduled, electric train service began to suburban Philadelphia communities, and electric multiple-unit passenger cars were intended to replace steam on these lines. These multiple-unit passenger cars accelerated faster and afforded passengers other amenities such as electric heat and reduced noise and smoke.

No. 800 and other Reading multiple-unit cars had spring-loaded high-voltage bus connectors on the roof that energized the other cars when contact was made. This permitted the operation of a multiple-unit train with only one, but typically two, pantographs raised – a departure from needing every pantograph raised. This virtually eliminated sparking and reduced wear and tear on the overhead wires.

Fun Fact: A 10.8 mile commute from Philadelphia to Chestnut Hill that once took 40-44 minutes by steam train was reduced to only 29 minutes by electric train.

Locomotives – Steam

Class: 4-19

Built: 1941 by Erie City Iron Works, Erie, Pennsylvania to Heisler Locomotive Works specifications

Retired: c. 1972

Fireless steam locomotives use no fire to make steam. Instead, steam, generated by a stationary steam engine, is charged into the locomotive’s boiler, which heats up the water already in the boiler to make more steam. One advantage of the fireless locomotive is that it does not produce smoke or sparks, which is particularly beneficial when operating in industries where a fire hazard exists.

Despite its small size, No. 111 employs modern features similar to those of some of the world’s largest steam locomotives being built at the same time, including a welded storage tank, Timken roller bearings, and Walschaert’s type valve-gear.

Fun Fact: At the time of its donation, this locomotive was still in serviceable condition and was used as an emergency backup engine at the Bethlehem Steel’s Bethlehem Plant.

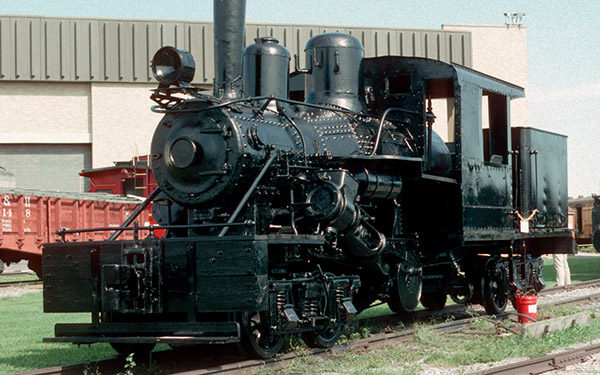

A New Type of Geared Locomotive

Class: 53-8-38

Built: 1918 by Heisler Locomotive Works, Erie, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1965

The Heisler featured three features that set it apart. The first was a “V” type engine similar in concept to an automobile. The second was its use of connecting rods on the outside of the truck frames to power the second axle. The third was the use of a heavy-duty gear case to protect the gears and ensure longevity. The latter made it especially suited for mining and quarry operations.

The Heisler worked for several different owners during its lifetime and became the first locomotive purchased by the Commonwealth for the Museum.

Fun Fact: This locomotive is one of only 35 Heisler products of the Company known to survive today.

Moving Lumber from Forest to Mill

Class: 65-3

Built: 1906 by Lima Locomotive & Machine Company, Lima, Ohio

Retired: c. 1964

Ephraim Shay, a Michigan lumberman, needed to find a way to move timber as cheaply as possible in any type of weather. He set to work developing a locomotive that could operate a heavy train over light rails, steep grades, and sharp curves, while remaining relatively inexpensive to build and maintain. He took his design to the Lima Locomotive Works and launched the beginnings of the remarkable, hard-working Shay locomotives.

The Shay had a unique drive train with its pistons and drive shafts set off-center on one side, making maintenance easier. The No. 1 is one of the most common versions of the Shay with several added features: a firebox that could burn wood or coal; a syphon pump that could draw water from streams, and adjustable couplers to accommodate log cars with varying heights.

Fun Fact: Compared to a typical rod locomotive of the same power, a Shay weighed 54 tons less, was 20 feet shorter, and could pull 63% more up a 6% grade.

The “Poor Man’s Locomotive”

Class: Climax class B

Built: 1913 by Climax Manufacturing Company, Corry, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1956

Pennsylvania lumberman Charles Scott approached the Climax Manufacturing Company, makers of farm implements and oil-drilling rigs, to design a steam locomotive to help get timber off the mountain. They designed the Climax to be powerful, agile, cheap and even disposable. The Class “A”, their first design was among the most flexible and nimble locomotives ever built, making use of an offset bevel gear. It lacked only one thing – size.

The Class B solved that problem and could be built in sizes from 17 to 62 tons. No. 4 is a 40-ton Class B model.

Fun Fact: The Climax could climb steeper grades and navigate sharper curves than any other type of geared locomotive its own weight.

Class: 8-30

Built: 1939, by Heisler Locomotive Works, Erie, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1969

In an era when large industries often purchased their small switch engines, hired their own crews, and performed the work themselves, the fireless steam locomotives became very popular. Onsite boiler houses provided a steady source of steam, and the locomotives were like a thermos bottle on wheels, filled with enough steam to operate for several hours and undertake work in such areas as munitions factories and textile mills.

The Pennsylvania Power & Light Fireless Locomotive “D” was originally built and streamlined for its appearance at the 1940s New York World’s Fair to show off Heisler’s manufacturing capabilities. After the Fair it was put to use by the Hammermill Paper Company and later Pennsylvania Power and Light, outliving numerous other steam locomotives.

Fun Fact: This engine is the only 0-8-0 fireless, and ultimately, the largest one of its kind ever built.

A Tale of Two Locomotives

Built: 1940 (locomotive) 1927 (tender) by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

The original John Bull was purchased by the Camden and Amboy Railroad from British locomotive builder Robert Stephenson and Company. Shipped to America in parts, and without any instructions, young engineer Isaac Dripps assembled the locomotive in ten days. Many modifications were soon made, including a tender, a headlight, and the first cowcatcher.

When it absorbed the Camden and Amboy Railroad in 1871, the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired the original John Bull, restoring it for the Centennial Exposition in 1876. In 1884, the Pennsylvania Railroad donated the locomotive to the Smithsonian Institution, which allowed them to operate

it at fairs and expositions for more than 50 years. For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, preservation concerns prevented the railroad from operating the original John Bull, so they built a working replica, which also ran at the 1948-1949 Chicago Railroad Fair.

Fun Fact: The replica locomotive was used under steam for a 1946 Pennsylvania promotional film and at the 1948-49 Chicago Railroad Fair. Once in the collection of the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, the replica John Bull was restored and operated under its own power several times between 1983 and 1999.

The 0-4-0 Switcher: A Compact Powerhouse

Class: A5s

Built: 1917 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1956

Built to move railroad cars around, often assembling and disassembling trains, a switcher locomotive needed to be powerful, nimble, and compact. One of the heaviest 0-4-0’s ever built, No. 94 was capable of getting even hefty cars moving quickly – the result of the efficient 0-4-0 wheel arrangement that put all of the switcher’s weight on its drive wheels.

The tender paired here with No. 94 features the distinctive “slope-back” design, which allows for better visibility of the rear.

Fun Fact: Switchers have been described as the railroad version of the tugboat.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

A Fast Runner

Class: E6s

Built: 1914 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1956

On June 11, 1927, Charles Lindbergh was honored for making the first solo, nonstop, transatlantic flight. This event in Washington, D.C. was filmed by several news companies—many of whom sent their film by airplane to theaters in New York City. One company, the International News Reel Corporation, sent their film by railroad. The train, pulled by engine No. 460, raced toward New York City at a top speed of 115 miles per hour. Even at that speed, it was still beaten by the airplane. However, the films delivered by airplanes still needed to be developed, while the films aboard the train were processed en route and were shown in theaters first.

Fun Fact: No. 460 raced an airplane from Washington, D.C. to New York City to deliver newsreel footage of Charles Lindbergh’s “Welcome Home” reception.

The Standard Freight Locomotive

Class: H3

Built: 1888 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona Works, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1939

The Pennsylvania Railroad’s Class R (later H3) steam locomotives became the primary mainline freight locomotive. The Altoona Shops built more than 825 between 1885 and 1898. Its 2-8-0, or “Consolidation” type wheel arrangement became the most popular design for freight locomotives across the country.

The locomotive design was the first to introduce the Belpaire Firebox. Named for its inventor Alfred Belpaire, this design provided greater strength than previous designs and allowed for more space for steam, as well as more area for combustion.

Fun Fact: By 1924, the Pennsylvania Railroad had over 3,300 class H locomotives in service, which accounted for 44% of its entire locomotive roster. No. 1187 remains the sole survivor of the Class R (reclassified H3 in 1897).

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

No. 1223: An “American” Star

Class: D16sb

Built: 1905 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1950

The durable 4-4-0 had nation-wide appeal through most of the 19th-century, earning it the name “American.” The Pennsylvania Railroad perfected its design, creating the D16 class as the most modern American-style locomotives ever built. No. 1223 pulled passenger trains on Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey lines for 45 years.

The locomotive was retired in 1950 and later borrowed by the Strasburg Rail Road beginning in 1960. It would once again return to steam service in 1965. It also pulled daily tourist trains and special excursions on the Strasburg Rail Road from 1965 until 1989.

Fun Fact: This locomotive had a star-lit career, appearing on the silver screen in Broadway Limited (1941) and Hello, Dolly! (1969), as well as several television documentaries and commercials.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A Standard Freight Locomotive

Class: H6sb

Built: 1905 by Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1956

At the dawn of the 20th century, the Pennsylvania Railroad billed itself as the “Standard Railroad of the World,” emerging as a clear leader in American railroading. Most of the road’s freight trains were pulled by various “H” class locomotives. Even among a class of 2,029 units, no two H6 locomotives were exactly the same.

No. 2846 received special accessories over its lifetime. These included: a superheater to further dry the steam on its path between the boiler and the pistons; a power reverse lever on the engineer’s side; and a rare pipe from the steam dome to the pilot wheels on the fireman’s side used in winter to discharge steam over frozen switch points.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Power for the Masses

Class: G5s

Built: 1924 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1955

The popularity of commuter trains brought about the development of the G5s, the largest and heaviest ten-wheelers ever built. They filled the need to combine high-speed service with the demands of frequent starts and stops. Designed by Pennsylvania Railroad mechanical engineer, William Kiesel, this compact locomotive was capable of rapid acceleration with a heavy train.

Originally planned for the Pittsburgh area, G5 class locomotives soon began operating in Philadelphia, Chicago, Long Island, and Grand Rapids. From big cities to small towns, the G5 became part of the daily routine for millions.

Fun Fact: The G5 was the standard Pennsylvania Railroad steam locomotive for commuter service for two decades.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The World’s Fastest Locomotive

Class: E7s

Built: 1902 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Juniata Shops, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1934 (original) 1939 (No. 8063)

Speed became a marketing tool as railroads competed for passenger business. The New York Central was the first to break the 100 mph barrier, but not long after, the Reading Company had four Atlantic-type locomotives equally capable. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s E2 and E3 class Atlantics quickly developed a reputation for being fast, dependable runners.

The E2 No. 7002 gained fame on June 12, 1905, when it reportedly set a ground speed record of 127.1 mph, making up time west of Crestline, Ohio. In 1939, the Pennsylvania Railroad prepared to send No. 7002 to the World’s Fair in New York, only to find it had been unceremoniously scrapped. The Pennsylvania Railroad chose another locomotive, No. 8063 as a “stand in” at the Fair. With no time to change its appearance, it debuted as No. 8063. In 1983, it was leased to the Strasburg Rail Road, where it operated until 1989.

Fun Fact: By the 1949 Chicago World’s Fair, the locomotive was shown off in all its glory as No 7002, under the banner of being the World’s Fastest Locomotive.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

A Compact and Powerful Workhorse

Class: B4a

Built: 1918 by Philadelphia and Reading Company, Reading Shops, Reading, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1963

The compact and reliable No. 1251 served for 45 years in the Reading Locomotive Shops. Known as a roundhouse “goat,” the No. 1251 was an industrial switching engine used to move locomotives in and out of the shops. Since the Reading shops built more than 620 completely new locomotives and rebuilt hundreds of others, No. 1251 was kept busy for many years.

The saddle tank switcher was designed with the water tank and fuel bins on the locomotive itself, adding more weight for traction. Compact in size, these engines were perfect for work around industrial areas and shops.

Fun Fact: No. 1251 was the last standard-gauge steam locomotive in daily operation on a class one railroad in the United States

Built in Pennsylvania: Used in Nevada

Class: 8-28d Mogul

Built: 1875 by Burnham, Perry, Williams & Company, (Baldwin Locomotive Works), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1944

The Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia led the world in locomotive production for half a century. With 1,445 employees in 1870, Baldwin was building hundreds of locomotives each year, including this one built for the Virginia and Truckee Railroad in Nevada, where it hauled silver ore and bullion from the mines of the Comstock Lode.

The ornately decorated “Tahoe” once featured brass trim, finished woodwork, gold leaf, and a bonnet style smokestack (an original feature that was restored) as part of the original Baldwin paint scheme, typical of the “Mogul” 2-6-0 locomotives of the 1870s. During its lifetime, No. 20’s fuel supply changed from wood (1875) to coal (1907) to oil (1911).

Fun Fact: In the 19th century, Baldwin Locomotive Works built thousands of steam locomotives that were operated throughout the United States and around the world.

Built: 1883 by Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1944

Olomana spent its life moving four-wheeled railcars piled high with cut sugar cane from the fields to the refinery. Because of its small size and relatively light-weight, it would be relatively easy to move on temporary tracks from one field to the next.

Since Olomana is a tank engine, it carries its fuel and water on the locomotive itself. The fuel, which was originally coal, was stored at the rear, and the water was carried in the U-shaped “saddle tank” that drapes over the boiler.

Fun Fact: Olomana arrived in California in the late 1940s after its purchase by Gerald Best. Best and, Disney animator, Ward Kimball restored and operated the locomotive on Kimball’s private railroad. A frequent visitor to the railroad was Kimball’s boss, Walt Disney, who occasionally operated the locomotive.

Cars – Passenger

Birth of the Modern Passenger Car

Built: 1836 by Camden and Amboy Railroad, Bordentown, New Jersey

Retired: c. 1865

Treasured as the second oldest passenger car in America, the No. 3 coach is noteworthy for its swiveling four-wheel trucks, modern seating and center-aisle arrangement. Earlier cars resembled stagecoaches; this car has more seats –24 bench seats compared to 6 – arranged in two rows along the windows. The central corridor allowed the conductor to collect tickets on board while doors on either end sped up boarding and exit times and gave the conductor control of access to the car. These features created the basic design and function of the passenger car.

The No. 3 and its sister coach accompanied the John Bull and later its replica at various World’s Fairs and expositions throughout the first half of the 20th century. It was donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1960 before being placed on long-term loan to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania. It is the oldest surviving eight-wheel passenger coach in North America.

Fun Fact: After retirement, the car was sold to a farmer who used the body as a chicken coop. It was acquired and restored by the Pennsylvania Railroad for exhibition at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

A Combination Baggage Car and Passenger Car

Built: 1855 by Cumberland Valley Railroad, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1909

The Cumberland Valley was one of Pennsylvania’s earliest railroads, chartered in 1835. The line gained great importance during the Civil War, shuttling troops and supplies toward the front line in the South. This car may have played a role in that effort. It became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s “relic” collection and was displayed at numerous expositions and public events.

This car is a combination passenger coach and baggage car. It incorporates an unusual walkway alongside the baggage compartment, a feature that may have been added after it was built. There is also an extra baggage-room window along the gallery.

Fun Fact: This car is believed to be one of the oldest surviving wooden passenger cars in the United States.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The Specialized Baggage Car

Class: BA

Built: 1882 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1909

From the earliest days of railroading, merchants recognized the appeal of using the fast passenger train schedules for shipping. As business flourished, the railroad developed specialized baggage cars to handle everything from passengers’ luggage to express parcels. An on-board baggage handler ensured that all baggage arrived safely at the proper station.

Baggage cars were usually grouped at the “head end” of the train immediately behind the locomotive, for safety, security, and ease of unloading. Once railroads began hauling valuable shipments, they installed bars in windows, strong locks on doors, and provided baggagemen with firearms for protection.

Fun Fact: Before it was restored for an appearance at the 1940 New York World’ Fair, the No 6 was stripped of its trucks and used as a storage shed and yard office in Wilmington, Delaware.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Steel Becomes the New Standard

Class: P70

Built: 1928 by Standard Steel Car Company, Hammond, Indiana

Retired: 1967

Steel cars became the new standard for safety and service, as well as durability and cost-effectiveness. The original steel cars followed the designs of earlier wooden coaches. Engineers quickly saw advantages in the new construction methods that made cars longer, lighter, long-lasting, and cheaper to build. The new cars could be modernized with lounges, observation sections, air conditioning, steam heat and rotating seats.

The Pennsylvania Railroad quickly set the standard for all-steel service, ordering passenger-baggage, baggage-mail, mail, and dining cars of similar construction. The Pennsylvania Railroad used several manufacturers to build a total fleet of over a thousand P-70 coaches.

Fun Fact: Railroads across the country followed the lead of the Pennsylvania Railroad, soon advertising all-steel service nationwide.

The New Model for Safety

Class: P58

Built: 1906 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1930

Prompted by the enormous safety hazards of coal-burning steam locomotives using the new Hudson River Tunnels, the Pennsylvania Railroad developed the first prototype of its new steel passenger cars. The No.1651 proved unsatisfactory as a genuinely “fireproof” car, because of the amount of combustible materials still present. As a result of this dissatisfaction, it was the only one of its kind ever built, though it paved the way for a new production model.

Although there were combustible materials still in the car, most were treated to resist flame. Steam heat replaced the coal-fired, pot-bellied stoves, and electric lights replaced oil lamps. To minimize the dangers of “telescoping,” the engineers had specially designed enclosed vestibules at each end of the car. For public comfort, the No. 1651 had both reversible and non-reversible seats, restrooms, and drinking water.

Fun Fact: Despite the enhanced safety, some passengers initially refused to ride the new steel cars for fear of lightning strikes.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The Late 19th Century Passenger Train: Elegant and Dangerous

Class: PF

Built: 1886 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1915

The late 19th century passenger train featured many elegant details: stained glass clerestory windows, golden oak paneling, silver-plated chandeliers, and rich, red plush seat cushions. No. 3556 also had toilet facilities and a brass spigot connected to a water tank for drinking water.

Despite their opulence, however, these wooden cars were always a safety hazard. The impact from train collisions could cause an engine to “telescope” another coach from the rear, crushing passengers and upsetting hot stoves, setting the cars ablaze. The development of steel body passenger cars in the early 20th century made train travel much safer, and the No, 3556 was replaced by an all-steel passenger coach.

Fun Fact: In the days before coolers and bottled water, passengers could refresh themselves by sharing a common drinking cup onboard.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The Versatile Combine

Class: OG

Built: 1895 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1939

Whether for business or pleasure, cross-country or cross-county, the choice for travel was the train. Comforts and convenience could vary widely on passenger trains. One of the most accommodating cars was the combine, a combination of both a passenger coach and a baggage compartment. These cars were a common feature on Pennsylvania’s passenger trains from the luxurious Pennsylvania Special to the tiniest of locals. The baggage compartment also had pigeonholes for small express packages, and at times, it would carry mail.

Within ten years of building the No, 4639, the Pennsylvania Railroad abandoned wooden passenger car construction in favor of stronger and safer steel.

Fun Fact: In some cases, the car was put at the end of mixed freight/passenger trains and used to carry passengers in addition to the rear-end train crew.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Mail by Rail

Class: BC

Built: 1893 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1939

Railroads began delivering U.S mail in their earliest days, initially hauling mail in bulk. In 1864, postal clerk George Armstrong initiated the idea of sorting the mail in transit, and the Railway Post Office concept caught on quickly. Railroad postal workers picked up the mail at station stops or grabbed it en route from a mail crane with a long metal hook. They sorted it into racks and pigeonholes in the car for either direct delivery or transfer to another train or some other mode of transportation.

In 1871, the Railway Mail Service employed 650 clerks in Railway Post Offices traveling more than 12 million miles a year. By the 1950s, air travel and automated sorting machines began moving mail faster than the Railway Post Office. The last run of the Railway Post Office was in 1977; although, bulk mail was delivered by Amtrak until 2004.

Fun Fact: This car is the only known railway postal car lighted by the Frost Carburetter System of Car Lighting, which ran on gasoline and lighted each car independently with a “vastly enlarged volume of light.”

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The Express Car

Class: BD

Built: 1899 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1939

Mail and express shipments made up some of the railroad’s most lucrative business. The railroad companies developed the express car to handle high value shipments, adding heavier doors and locks and fewer and smaller barred windows. The railroad leased this car to the Adams Express Company, a forerunner of the Railway Express Agency, and later FedEx or UPS

Adams Express Company further modified No. 6076, adding small ventilators, floor drains, and a gutter running down the center of the interior. These changes indicate that the car saw service as a market car, hauling produce. Sometime after 1919, No. 6076 became a tool-and-block car used for maintenance-of-way service.

Fun Fact: To increase security for the express shipments, this car’s side windows were replaced with air vents.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Steps Toward Greater Safety

Class: PH

Built: 1896 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Columbus, Ohio

Retired: 1939

As the 19th century grew to a close, railroads were increasingly under attack by lawmakers and the traveling public, demanding greater safety. The No. 8177, though still primarily constructed of wood, added several safety appliances. These included the automatic coupler and air brake, now mandated by federal law.

An early semi-enclosed vestibule provided protection from the elements and the rocking of the train as passengers and crewmembers crossed between cars. A ladies’ lounge area and separate bathrooms at opposite ends of the car for men and women also provided privacy. These improvements provided a smoother and more comfortable ride as well. As with many other wooden passenger cars, No. 8177 was transferred to maintenance-of-way service in the 1910s.

Fun Fact: The No. 8177 was restored for service in 1982 on the Strasburg Rail Road and was last used in 1987 as part of the 75th anniversary of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broadway Limited.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The All-Important Baggage Car

Class: B60b

Built: 1928 by St. Louis Car Company, St. Louis, Missouri

Retired: 1985

Baggage cars had a variety of uses on American railroads. The staff included a baggage clerk and his staff of handlers to handle shipping crates, mail bags, express packages, steamer trunks, and parcels. They hauled the load on a motorized wagon to the loading platform where strong backs heft the varied cargo onto the car.

In some cars, such as the No. 9356, the work was carried out en route, requiring a work desk, pigeonhole sorting racks, steam heat, electric lighting, water cooler, safe, and a restroom for the agent.

Fun Fact: The 6-inch gold star on the side over the number indicated that this car was equipped with a toilet and locker for a messenger or baggageman’s use.

Click Here for Virtual Tours of the Sleeping Berth, Seats, Kitchen, Men’s Room, Women’s Room & Dining Area

Class: P5

Built: 1913 by Pullman Company, Pullman, Illinois

Retired: 1967

The Lotos Club, named after a fashionable men’s literary club in New York City, is typical of the all-steel sleeping and lounge accommodations of the heyday of railroad travel. These cars came in many different dining and sleeping arrangements and ran on different railroads. They were noted both for comfort and the fine service of the Pullman Porters, African-American men hired by the Pullman Company to serve as sleeping car porters.

The club-type cars were placed wherever and whenever they were needed, often offered for use for private parties. Family and friends of Elmer Layden, one of the famed “Four Horsemen” of Notre Dame, leased this car for its final run from Chicago to South Bend for a Notre Dame football game.

Fun Fact: In the 1920s, the Pullman Company was the largest “hotel operator” in the country, sleeping 100,000 guests every night in nearly 10,000 cars.

The Exclusive Business Car

Class: PV

Built: 1914 by Pullman Company, Pullman, Illinois

Retired: early 1960s

The business car was designed as a mobile office for high-ranking railroad executives. No. 203 was built for the use of Carl R. Gray (1867-1939), president of the Western Maryland Railroad and other senior officers. It included accommodations for up to four executives, with a dining room, kitchen, pantry, crew quarters, lounge and two master bedrooms, each with a shower. The interior was remodeled in 1954 by Dorothy Draper, decorator of hotel and automobile interiors.

Business cars were used to entertain clients, prospective shippers, customers, and business partners, as well as the occasional perk of a private excursion. It was also used to observe the condition of the track and the performance of the train crew. An onboard staff consisted of a train secretary, steward, and chef. The Rockefeller family were frequent guests, and were said to have filled the observation room with a large sandbox when their young grandchildren were along.

Fun Fact: Carl Gray specified sheathing that looked like wood on the exterior to resemble the business cars of the larger railroads.

Cars – Freight

Early Tank Car

Class: TM

Built: 1939 by American Car and Foundry Company, Milton, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1970

Pennsylvania, the state with the first oil well, also built the railroad tank car. The early design had two large vertical vats on a flat car. It evolved into horizontal iron and, later, steel tanks with one or more domes to facilitate loading and allow for expansion of liquid during travel.

The American Car and Foundry Company, which had its origins in Milton, Pennsylvania, became one of the nation’s largest builders of tank cars. This car consists of three separate compartments, each equipped with its own dome and unloading port. It could haul multiple cargoes on a single trip and could also be loaded and unloaded quickly. Heating coils kept its lading fluid in colder months.

Fun Fact: Tank cars had to travel either at full capacity or empty, since the movement of liquid inside the tank could derail the car.

The “Composite” Boxcar

Class: XM

Built: 1907 by American Car and Foundry Company, Berwick, PA

Retired: c. 1970

Boxcar No, 19607 uses both wood and steel in its construction. The tongue-and-groove wood sheathing covers a steel frame. The roof of the car is also made of steel for increased durability.

Steel frames were standard by 1940, providing strength and sturdiness. Wood, however, was less expensive and easily replaced.

Fun Fact: Before retirement, No, 19607 was used as a tool car in a work train.

Keeping Produce Cold: A Diet Revolution

Class: RS

Built: 1928 by Fruit Growers Express Company, Alexandria, Virginia

Retired: c. 1975

Imagine the wonder of making fresh fruits available year-round! Before the advent of the “reefer” (refrigerated car) Americans were limited to foods that could be grown locally. This new transportation technology not only kept produce fresh but also revolutionized the meat-packing and brewing industries by centralizing production.

Before mechanical refrigeration, ice was the key. Workers loaded blocks of ice through roof-top hatches. As the ice melted, the water drained through chutes in the corners. Insulated walls, three inches thick, and a built-in circulating system driven by the car’s wheels cycled the cool air from floor to ceiling.

Fun Fact: Workers added salt to the ice to make it melt faster thus making the ice cooler.

A Typical Coal Hopper

Class: HM

Built: 1952 by American Car and Foundry Company, Huntington, West Virginia

Retired: 1969

From the 1920s to the 1950s, hopper cars like this one carried most coal, stone and sand. The typical car was 34 feet long, had two hopper bays on the floor, and held 50 tons of coal. This car has its structural supports on the inside of the steel sheathing, allowing for slightly greater capacity.

The Lehigh & New England Railroad was one of many railroads built to carry the anthracite coal reserves of eastern Pennsylvania with numerous branches to mines and quarries. The railroad ended its operations in 1961 after the use of anthracite declined.

Fun Fact: This car was later used at Pennsylvania Power & Light Company’s Hauto Power Plant to transport coal used to generate electricity.

The Versatile Boxcar

Class: XM

Built: 1935 by Lehigh Valley Railroad, Sayre, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1970

To many, the boxcar is the most recognizable freight car – and the most versatile. It might be found carrying lumber, paper products, all kinds of manufactured products, or even foodstuffs. In the early 20th century, car builders developed standard designs and construction methods for boxcars. During the depression era, workers recycled older materials, sometimes building longer cars with greater capacity.

The numbers and abbreviations on the sides of the cars help railroad crews to identify and track rail cars. These markings include: the car number, weight data as well as build and service information, all in a language well known to railroad workers.

Fun Fact: This car was once equipped with loading hatches on the roof for hauling grain.

The PS-2 Covered Hopper

Class: H34a

Built: 1955 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1999

The Pullman Standard Company developed common design and construction techniques that standardized rail cars of all kinds. The covered hopper carried bulk commodities of cement, sand and other dry aggregates in hoppers that could be found on railroads large and small.

The Pennsylvania Railroad Company ordered 400 Pullman Standard cars as kits and sent them to their own large shop complexes for assembly. Pullman Standard built an additional 300 cars for the Pennsylvania in their own Butler, Pennsylvania facility.

Fun Fact: The car was marked with a yellow “S” by Penn Central to denote the fact that it was used by the company’s “S”tores department, which used it to haul locomotive sand to terminals around the system.

The Ore Jenny

Class: G39a

Built: 1964 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1998

Iron ore, essential in steel production, is one of the heaviest products to be shipped by rail. Specialized cars, known as “jennies,” were built to replace open hoppers in transporting this commodity. The smaller jenny was cheaper to build and maintain, as well as lighter and more efficient to operate. Jennies were unloaded by rotating upside down in a rotary dumper.

In winter, railroads needed to find solutions to deal with the tendency for ore to freeze inside the cars. They tried coating the exterior of the cars with foam to prevent freezing and inserting steam pipes into pockets to thaw frozen loads.

Fun Fact: Despite its small size, this ore jenny could carry up to 70 tons of iron ore.

Insulated Boxcars

Class: X54

Built: 1960 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania

Retired: c.1995

Though they all share a common design, boxcars come in a wide assortment of sizes and adaptations to haul a variety of goods. This boxcar is designed to carry perishable foodstuffs. While meats, dairy, and produce products need extreme temperature control, some foods, such as canned goods, require more modest protection. These cars feature a heavy layer of insulation, tight-sealing doors, and a cushioned underframe.

These small cars are only 40 feet in length inside. They may have been specifically designed to meet the needs of the shippers’ loading doors.

Fun Fact: X54’s were equipped with the Evans Quick Loader, a device consisting of two gates mounted on the ceiling of the car which could be brought down like garage doors and positioned to secure the car’s contents in place.

The Arrival of the Steel Hopper

Class: GL

Built: 1898 by Schoen Pressed Steel Company, McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania

Retired: c.1939

Railroads began experimenting with steel cars in the late 19th century, searching for ways to increase payload and reduce maintenance costs. The first problem to be solved was how to reduce the weight of steel. Innovations with pressed steel forms lightened the cars while still maintaining structural integrity. A steel car only 2 tons more than a wooden car increased capacity by 10 tons!

Larger and stronger cars soon led to larger locomotives, longer trains, and heavier rail and bridges. The Pennsylvania Railroad quickly led the way in construction and ownership of the new all-steel hoppers.

Fun Fact: This hopper car, No.33164, is the earliest all-steel Pennsylvania Railroad freight car in existence.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

A Pioneer Hopper

Class: GG

Built: 1895 by Barney and Smith Car Company, Dayton, Ohio

Retired: c.1939

The Pittsburgh, Youngstown and Ashtabula Railroad connected the steel mills of Pittsburgh with the shores of Lake Erie. Their primary commodity was coal. Early coal hoppers were made mostly of wood, lacking the capacity and endurance of the steel hoppers to come.

The prototype for this car was known as the “Potter Gondola Car,” named after Pennsylvania Railroad Superintendent, G.L. Potter. It features sloped end sheets and discharge doors that assist unloading with the help of gravity. This was a first step in the evolution of hopper cars from gondolas.

Fun Fact: This is the oldest Pennsylvania Railroad freight car in existence.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Cars – Other

Clearing the Rails

Built: 1897 by Ensign Manufacturing Company, Huntington, West Virginia to Russell Snow Plow Company specifications

Retired: 1945

Heavy snowfall and icy weather could bring a railroad to a halt, disrupting both freight and passenger service. Snow plows were the railroad’s first line of defense in a raging snowstorm. Early wedge plows attached to engines were considered dangerous if it were to hit a fallen tree or hidden debris on the track. The design of this Russell snowplow allowed for greater visibility, giving a crew member perched in the pilot house the ability to see obstructions ahead, and increased strength with its heavy, timber-frame construction.

The Coudersport and Port Allegany Railroad snowplow was designed for single track use and includes a “flanger” underneath that removed snow and ice from the insides of the rails. The flanger could be raised or lowered to avoid damaging switches and grade crossings.

Fun Fact: This snowplow, designed to clear the track safely, may be the oldest snowplow still in existence.

Class: ND

Built: 1913 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1954

Introduced in 1903, the ND class cabin or caboose was the first to use steel in its under frame. Previous cabooses used only wood. Although only used in the under frame, the use of steel added strength to the car and gave the crew some measure of protection if struck from the rear.

Cabooses were designed so that the crew could observe and protect the train and its contents from damage. They were also used as rolling offices for freight conductors and as quarters for the crew. Since cabooses were only intended for the crew and not for the movement of goods, they were considered non-revenue equipment, which meant they made the railroad no money. For this reason, railroads were slow to adopt steel in their construction.

Fun Fact: The steel under frame was reportedly designed to withstand the stresses of two H6 class steam locomotives (the large freight locomotives of the era) pushing behind the caboose.

The Bobber Caboose: An Office on Wheels

Built: c. 1890 by Lehigh Valley Railroad, Packerton, Pennsylvania

Retired: c. 1937

The caboose served as the conductor’s office. Here he kept track of the train’s paperwork, including its freight shipments. The car also provided accommodations for long journeys and nights away from home. The conductor often shared this office with a brakeman who assisted in throwing switches, coupling cars and protecting the end of the train.

With a short, rigid, four-wheeled truck and un-cushioned couplers, this type of caboose earned the nickname “bobber,” referring to its rough ride. Fortunately, “bobbers” were usually limited to slower and shorter branch line runs.

Fun Fact: After its retirement, this caboose, stripped of its wheels, became a watchman’s shanty, a storage shed, and finally a playhouse for kids known as “Aunt Clara’s Caboose.’

A Popular Redesign

Class: N5c

Built: 1942 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1985

World War II put great stress on America’s railroad with the need to move more freight and passengers than ever before. With the entire economy turned toward wartime production, railroads had to use readily available materials to build new rolling stock. This car provides a clear example with its four porthole windows on each side, making use of glass manufactured for battleships.

This caboose outlived the Pennsylvania Railroad and would end its service, along with most cabooses during the 1980s and 1990s. Cabooses were replaced by an End of Train device (EOT), which was attached to the last car of the train. This device flashed a red light, marking the rear of the train, and sent critical train operating information to the crew. This light-weight and inexpensive device eliminated the expense of manning and maintaining a heavy car, which made the railroad no money.

Fun Fact: When train crews were assigned to a particular caboose, many added their own décor, personal comforts, and even pin-up art.

A Car to Test the Scales

Built: 1891 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Retired: 1989

Because railroads often billed clients on the tonnage of goods handled, it was necessary to have accurate scales built on special sidings. Scales needed to be calibrated on a regular basis. Specially-designed cars were built to maintain a fixed weight. They were built of metal to avoid splintering and absorption of humidity. Unnecessary shelves and ridges were eliminated, and even air brakes were omitted to avoid variance in weight.

Once weighed in on a master scale, the maintainers sealed and locked the car’s compartments. It was then ready to serve as a test car to assure the accuracy of the scales. The sound construction and regular maintenance led to the car’s unusually long service life.

Fun Fact: When retired, this scale test car was the oldest car in continuous service on a Class 1 railroad in the United States.

The Instruction Car

Built: 1910 by Pennsylvania Railroad, Altoona, Pennsylvania

Rebuild date: 1928

Retired: 1966

One of the most critical components on any train is its brake system. An employee’s knowledge of the proper use and maintenance of these complex systems could mean the difference between life and death. Consequently, railroads required employees to complete training and exams on a two-year schedule. To reach the thousands of employees across the Northeast, the railroad sent the instructor and the classroom to the students.

In 1928 The Pennsylvania Railroad rebuilt a former Railway Post Office into Instruction Car No. 492445. The interior of the car includes an instructor’s office and walls lined with cutaways and working examples of each type of brake system in use on the railroad. The car’s restoration is one of the most thorough and historically documented projects at any railroad Museum to date.

Fun Fact: This traveling classroom was once outfitted to simulate a fifty car freight train, helping to keep railroad employees system-wide up-to-date on air brakes, saving time, money, and ultimately lives, as the result of regular, hands-on training.